02 November 2020

|

Surplus population

From an underground broadsheet to a baroque adventure board game played as members of the marginalised underclass, Sean Aaberg invites us to shake the hand of doom

Sean Aaberg got into punk in 1988 at the age of 12, and it saved his life. Being part of the DIY scene made what followed that much more obvious. If you want to do something, you’re going to learn how to do it, then do it. After meeting Katie, his chief collaborator and now wife, they set up Goblinko, a punk art store. The store was originally created to support Pork, a free magazine that can best be described as an underground broadsheet, a counter-cultural throwback to the punk magazines of the 80s and 60s free magazines. It blew up.

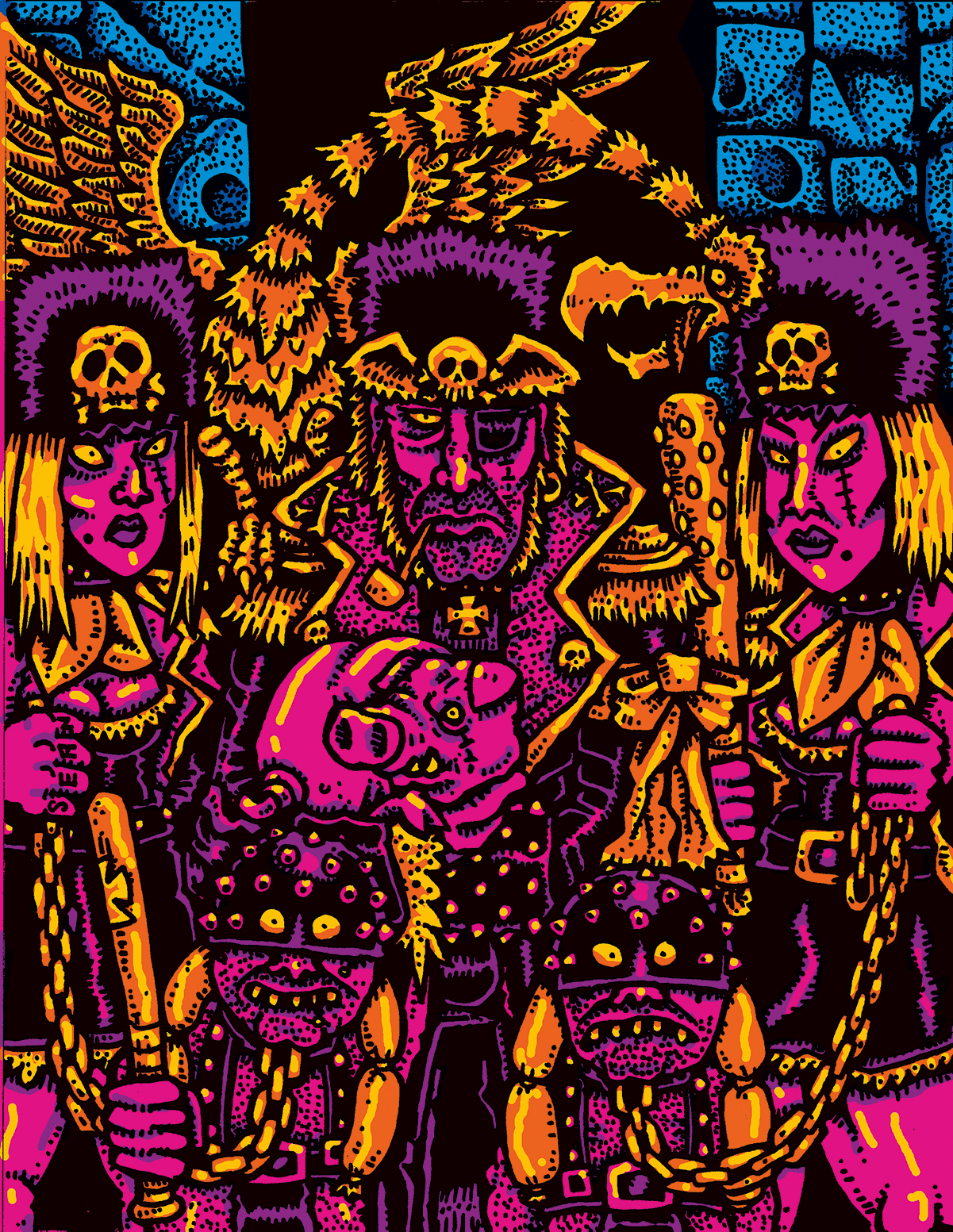

And now, Dungeon Degenerates: Hand of Doom, is available on a wide retail release after its second Kickstarter, meaning we can all get deep into the world that Aaberg has created for us. And what a world. Vivid, neon-punk art and a world deep and rich with its referenced connectivity, it gives you as much as you put into it. It looks wild and plays wild. It’s a game known for its complexity and crunchy depth, but rewards you if you approach it right.

“We use corny fantasy tropes but modify them enough that they’re exciting again. You basically play, like – I want to use this dumb Dickensian term – which is ‘surplus population’. The government of the Wurstreich is so corrupt that they’re just throwing people in the jails to rot. So, it’s kind of like America right now, where like people that have no place being in jail end up in jail,” says Aaberg, “and you’re basically trying to find your way in the world. Meanwhile, everything’s falling apart – wizards and monsters are trying to take over the land.”

The land itself, a lairy map of sprawling toxic coloured regions and towns, scrawled with prurient details, throbs with Aaberg’s influences. “I consider myself a kind of conceptual artist, but my main artistic skill is in illustration,” says Sean when I try and pin down where his art style sits, which particular sub-genre cave of electric-punk rave-metal it crawled from, “it’s funny, I’m not supposed to describe my art to people because they’re just supposed to understand it themselves. But then again, because I’m a self-promoter, I have to be able to talk about it in general. I feel like my main influences are the underground comics of the 60s through the 80s. And the colour scheme is inspired by Marvel comics from the 70s and 60s. And psychedelic posters from the 60s. And also the black light posters from the 70s.” He says, also mentioning the likes of Robert Crumb’s stoner Zap Comix.

And like everything in the world of tabletop gaming, Games Workshop makes an appearance in his list of influences. Robert Blanche and Gary Chalk are cited as offering the metal weirdness. “It was pretty unusual back in the day” says Aaberg. Games Workshop took their art more seriously than other companies – great cover art with little inside was the norm. Games Workshop on the other hand put huge effort into bringing their world alive. The breadth of the worlds of the various Warhammer brands is staggering for its completeness.

Dungeon Degenerates on the other hand is about the connective tissue with our own reality. With something like 40 characters now existing in Dungeon Degenerates, they all link back to parts of the story of Aaberg’s life, and the way he sees the world.

No Filter

There’s a certain auteur aspect to Dungeon Degenerates which rises above what is already an auteur heavy medium. Everything is connected through Aaberg, and the characters we meet in this world are probably the rawest presentation of aspects of his life.

“I was a street punk, so a lot of the people that I knew growing up were street characters – kind of weird people,” says Aaberg, “and you could see their potential, or their wasted potential I guess. This game tries to empower those people because it really feels like they’ve been pushed to the margins of reality these days, if not back then also. But it has been more pronounced to me as an adult or as a ‘responsible adult’. Big quotation marks.” He laughs.

The box comes with only a handful of characters like the Bog Conjurer, Void Witch, Hinterlander and Witch Smeller, amongst others. The Mercenary Alchemist is loosely based on Agrippa, a German alchemist from the 1400s who had a strong interest in the occult and satirised the state of the sciences. This, compared with the Iggy Pop inspired Bog Conjurer – a kind of swap wizard, and the Bloodsport Brawler – a lady wrestler who performs blood sport for the government as an act of blood and circuses, shows the breadth of reference in the game. Pop culture, history, and satire all blend here seamlessly.

The Witch Smeller, another character plays with ideas that dig into the world too.

“The basic idea of the game is you have an out of control Catholic church kind of deal. Like we had back in the 1700s and 1800s or whatever. And specifically it’s a Black Adder reference. There’s this episode called the Witch Smeller Pursuviant and I found it to be so funny. You have this arbitrary form of finding witches. They’d have those big fake noses. It worked with how popular those plague doctors are these days. I felt like having a big false nose was funny and people would find it amusing if they got the joke,” says Sean, “she essentially took an official Witch Smellers uniform and has been exploiting the leniency society has given those people to be invasive. She’s like a Batman or a vigilante character.”

These characters are subversive and from a class of people who are pushed out to the edges of society, but draw influences from what sometimes feels like undiscerned pockets of culture. And it’s all the better for it.

No-brow culture

In Aaberg’s imagination everything is equal, there is no high-brow, low-brow or otherwise.

“I found a niche for myself doing low-brow stuff, but I’m very high-brow when it comes to my own library, but it’s also got a lot of low-brow stuff in it. The main thing for me is I don’t distinguish and I just kind of like what I like and absorb what I absorb. There’s not a lot of distinguishing or segregation,” says Aaberg, “it’s funny, like I feel like a lot of society these days is very niche and very interested in segregating everything.”

The game is notable for its complexity. It’s a huge and gritty adventure which takes place in a world of many locations and monsters. There’s multiple decks to deal with, events, dice tests and complex interactions between monsters and loot. This all stems from the non-differntiation of the fidelity of a game on cardboard, and those produced digitally.

“The complexity comes from trying to provide players with a lot of options. I got into gaming in 1986 or so, and simultaneously video games were getting way better. I’ve watched both of those fields come up at the same time. I feel like I don’t really distinguish between the two, like in terms of my expectations,” says Aaberg.

The game takes place over multiple phases, the first a map phase which include selecting a stance, then resting or moving. The second is the ‘danger’ phase where a card is flipped, danger is increased in certain listed areas, then you compare your current threat level with it – if your current threat level is higher than that listed on the card, it’s time to draw some monsters from the deck and begin a complex form of combat. This again includes stances, power rolls, items, and ways to add more dice. Your damage will be measured out on the highest number of the roll-lower-than-your-stat test required. There’s also town levels relating to their safety and a bounty level to compare to, should you run into any member of the law. You don’t always have to fight, you can use bribery or the art of cowardice. Alongside this there are encounters that require choices from the party. Your choices at every point are huge and meaningful. It colours in your story in small strokes, creating a huge picture at the end.

And finally, on top of this, each mission you complete comes with a choice at its conclusion. Campaigns have a sense of choose your own adventure, depending on your abilities and choices. The opening mission sees you attempting to return a shaman’s head – either to the jailer that freed you, or to the stone circle (if you’re magic enough to understand it’s chatter). You can of course, just leave it where it is and make a break for it. The missions that follow offer you the chance to set up a base or pilgrimage to a far mountain – depending on your previous choices.

This all leads to what is a set of highly complicated rules, which, in the end, is part of the fun. Yes, it’s baroque, but it really depends on how you want to look at a game like this. Mechanically it might be seen as unwieldy, if you want to look at every game as a victory point machine. Instead though, when viewed as a work of epic fantasy fiction, it sings. It’s intentionally complex, which is refreshing in a world of Kickstarter games whose stretch goals leave the inevitable stretch marks of pledge promise bloat.

When asked if the game is an RPG, Sean flatly says “No.” Before continuing, “It’s RPG flavoured. We wanted to give people the experience of playing a roleplaying game without having to play a roleplaying game. We realized that roleplaying is for a very specific kind of brain. For people who like to tell stories in that certain way.”

This is in the services of the way we should be approaching the game “I think also having that RPG mentality while you’re playing helps the storytelling in general or having an imaginative sense of you when you’re going through the game helps a lot.” Says Aaberg, “I guess thinking more like the way you do when you read a fiction book, as opposed to an instruction manual. You know, I feel like it works better that way.”

And it works its way in in the same was as any work of fiction. You are drawn by the initial line, but by the end the whole work lives on in your mind. This is how Dungeon Degenerates is meant to stay with you, as it does with Sean.

“Once the world got established, it started to generate its own stories and characters and monsters. It has enough going on inside of it that it would make its own content essentially. Which is why I say – when people get it, when they really understand – they get that it’s essentially living as opposed to mechanical. It continues to live inside of you.”

What’s next

Aaberg is working on the follow up to Dungeon Degenerates, but having experienced a stroke in September last year which effects his left, drawing, side, he has been unable to dive directly into sketching for ideas. Instead he has been more restrained.

“It’s been good because it’s like I get to think about stuff a lot more, whereas before I would just be working so hard that didn’t have a lot of time to think about stuff. This way there’s more fleshed out concepts. And then because my brain works so fast, I’m coming up with maybe too much content for it. So, there’s a whole bunch of different games that are appearing,” says Aaberg. The game takes place in the same world, but on a different map – hoping to entice players back with something familiar while offering the surprises that we have come to expect from Dungeon Degenerates.

In addition to this, there’s a card game based on Dungeon Degenerates, called Dungeon Breakout. Designed to be a little more accessible, the game is focused on the initial escape from the dungeon and will be released in March 2020. There’s also a kids game in the works called Adventures of Pipu – based on a comic about a baby chick which he and Katie worked on when they first met. It might seem like a wild left turn, but to us? We can’t see the difference.

Words by Christopher John Eggett

This article originally appeared in issue 40 of Tabletop Gaming. Pick up the latest issue of the UK's fastest-growing gaming magazine in print or digital here or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Sometimes we may include links to online retailers, from which we might receive a commission if you make a purchase. Affiliate links do not influence editorial coverage and will only be used when covering relevant products

Comments

Login or register to add a comment

No comments